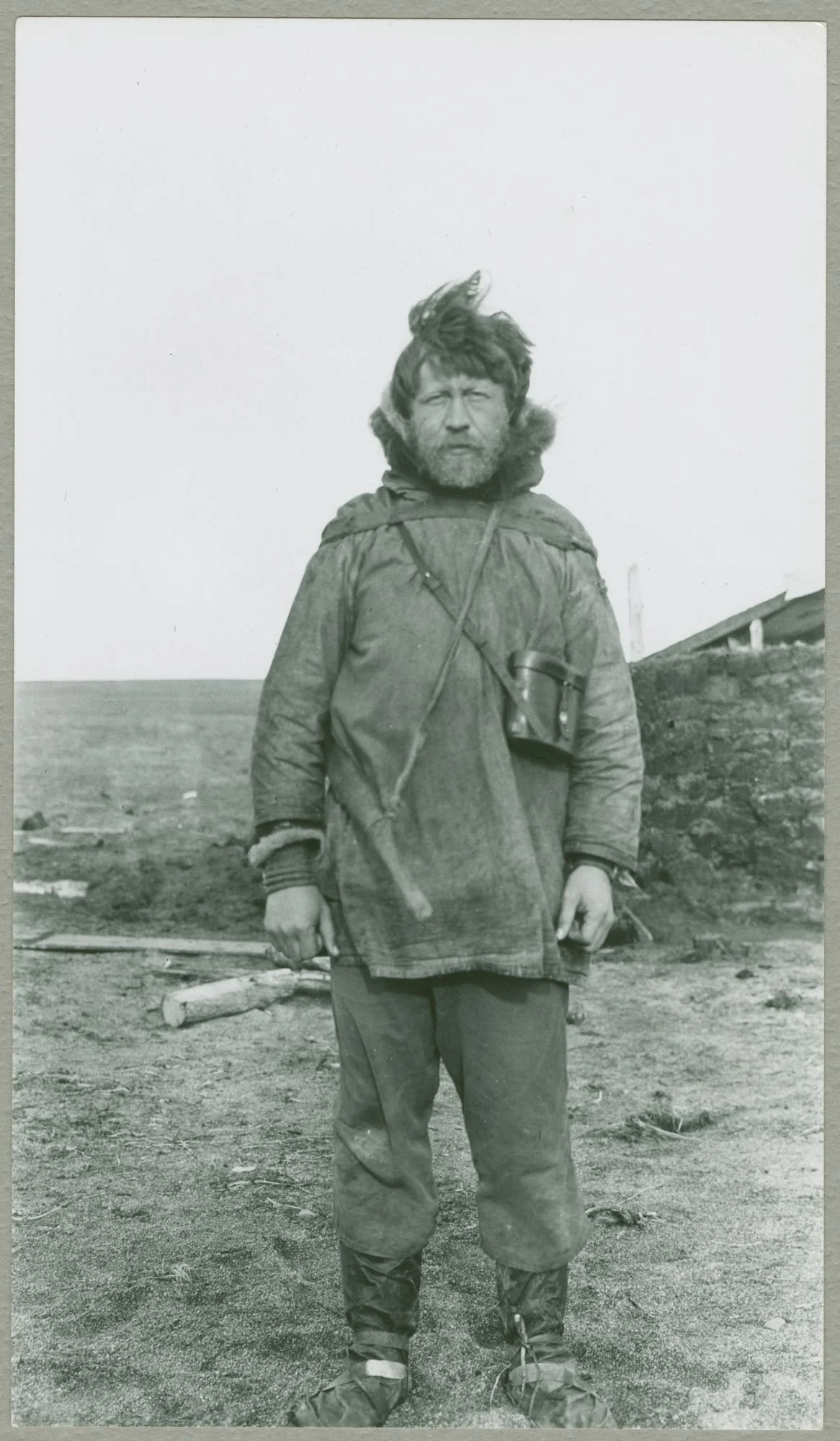

Photo courtesy of The Stefansson Collection of Arctic Photographs, Dartmouth University Archives

Photo courtesy of The Stefansson Collection of Arctic Photographs, Dartmouth University Archives

Vilhjálmur Stefansson

Explorer, Ethnologist, Writer

1879-1962

Arnes, MB; Mountain, ND

Dr. Vilhjálmur Stefansson was a renowned Arctic explorer, ethnologist, and writer. He is best known for his extensive expeditions in the high Arctic during the early 20th century. Stefansson carried out landmark mapping of the geography and waters in the Canadian North, discovering several new land masses under the ice which he claimed for Canada. He also published extensive ethnographic research on Inuit culture and lifestyle and suggestions for resilient adaptation for living well in the Arctic. Stefansson's adventurous spirit, scientific curiosity, and pioneering ideas have left a lasting impact on Arctic exploration and research, not to mention, the geopolitical landscape of the 21st century. Through his extensive writings and public lectures, Stefansson challenged the longstanding image of the Arctic as an inhospitable and barren wasteland, instead presenting it as a region filled with opportunity, resources, and the potential for human adaptation and prosperity.

Early Life and Education

Vilhjálmur Stefansson was born on November 3rd, 1879, in Arnes, Manitoba to Icelandic immigrant parents who had arrived in New Iceland with the ‘large group’ in 1876. His parents, Jóhann Stefánsson and Ingibjörg Jóhannesdóttir, suffered the tragic disasters that befell the fledging Icelandic community, losing two children to the smallpox epidemic, only to be flooded out the following year. Vilhjálmur was born at Arnes, just north of Gimli, Manitoba. His parents officially christened him with an angelized version of his name: William Stephenson. When Vilhjálmur was 18 months old, the family moved to North Dakota, where Vilhjálmur grew up on a farm in the Red River Valley, near the village of Mountain, Pembina County. The love of books and learning was deeply instilled in him by his father. Once in an interview, he remarked that his education was ‘typically Icelandic’. He learned to read sitting with the family in the ‘baðstofa’, reading the Bible out loud and listening to the sagas. Like so many Icelandic home-steading families, Jóhann and Ingibjörg did not have much money, but they had books. They loved learning and they loved debating ideas. His father held strong viewpoints concerning the new ideas circulating in the Lutheran church at the time that he would passionately defend. Vilhjálmur said he inherited a sense of conviction and determination from his father, along with a life-long love of learning.

Vilhjálmur may have also acquired his fiercely independent and tenacious spirit from his father: qualities that underlaid his courage to be an Arctic explorer but also which propelled him through hard times in his early life. Vilhjálmur was only 13 years old when his parents died. He went to work as a farm hand to make his keep and lived with his elder married sister. At this young age, he was already determined to go to university. He frugally put away savings to meet his goal. With working, he had little time for studies, but once he had saved enough money Vilhjálmur applied to the University of North Dakota. He only 27 months of formal education, which the university deemed was not enough. They admitted him on the condition he complete the four-year secondary school program. However, Vilhjálmur saw little point in spending years on secondary school courses, so he negotiated with the university entrance committee that he could be admitted on the condition that he pass the standardized entrance exams. He immediately passed the History and English exams and took the courses for Math and Science, while continuing to work to support himself. Vilhjálmur completed the required four-year program in two years, successfully passing the Math and Science exams, and joined the University of North Dakota freshman late in the fall of 1900. He came in late as he had to complete the haying season before commencing his studies. Vilhjálmur quickly became the centre of a lively and intellectually engaged group of freshmen, some of whom would remain life-long friends and colleagues. At this time, he officially changed his name to the Icelandic version to connect more deeply with his roots.

Vilhjálmur’s Icelandic roots were important to him and recognized in his biographers. W. J. Lindal, in the journal, ‘The Icelandic Canadian’, said Vilhjálmur represented “the Viking Spirit at its best.” Lindal explains that he is referring to the ancient Hávamal description extolling a character that strives “to understand the essence of things” and “to render the material environment conducive to better living.” Lindal is referring to Vilhjálmur’s scholarly aptitudes. Lindal argues that Stefansson’s qualities of ‘single-minded tenacity, scientific exactitude and idealism, combined with his prolific writing and his determined advocacy for Canada to recognize the potential of its Arctic regions, profoundly impacted the course of history. William Hunt in his biography of Stefansson, agrees that Stefansson had a strong scientific inclination which pushed him to search for a deeper understanding of how the Arctic might have a direct bearing upon the phenomenon of life and society.” However, Hunt added that an explorer has to have a certain egotistical and hard-nosed nature which often puts them at odds with authority. Even in his university days, Vilhjálmur’s single-minded tenacity was apparent. He was well-liked by his peers at the university, but sometimes he was a ‘thorn in the side’ to his professors. He was expelled from the University of North Dakota for helping out his friends on the football team with their German-language assignments. Vilhjálmur was offered an opportunity to redeem himself and instead, he and his friends carried out a pageant, where they put him in a wheel barrel, as if he was dead, and wheeled to edge of campus where they unceremoniously dumped him. He left university and spent the next year working for a local newspaper. Hunt goes on to say that “The episode did not chasten him particularly; rather, it provided a chance to prove that determined man could overcome obstacles set before him by people in authority and, more than anything, is expulsion created in him a sense of independence.”

Vilhjálmur’s uncompromising streak and determination to do things his own way surfaced again when he negotiated his way back into a different university a year later. He accepted to attend the University of Iowa on the proviso that he be given freedom in his studies. His precocious intellect, passion for learning and comprehensive grasp of subjects was recognized by his professors. He completed his undergraduate degree with the University of Iowa in 1903 and despite clashing with authority, Vilhjálmur received letters of recommendations for graduate school from professors at both the Universities of North Dakota and Iowa. His broad intellectual prowess and exceptional debating skills had also caught the attention of notable figures in the Icelandic Unitarian Church, who recognized his potential, and envisioned him as a promising candidate for the ministry. They funded his way to a church conference in Boston, and were so impressed with his performance, they offered Vilhjálmur a scholarship to Harvard for divinity studies. Vilhjálmur entered Harvard in 1903, where his remarkable genius was quickly noticed by Frederic Ward Putnam, the Head of the Anthropology Department and Director of the renowned Peabody Museum. He enticed Stefansson to switch faculties by offering him both a fellowship and a teaching position in his department.

Vilhjálmur took the opportunity to do his first fieldwork in Iceland. He had been intrigued by his mother’s accounts of how, in her community in Iceland, tooth decay was not a problem. She would often recount stories from her childhood, describing how the residents maintained healthy teeth despite limited access to modern dental care. According to her, their local diet was rich in fish, with limited whole grains. These anecdotes sparked his curiosity about the link between biological and cultural factors and led him to wonder what lessons could be learned from the Icelandic diet and way of living. It was the beginning of a life-long interest in nutrition, and gleaning knowledge from northern communities. In 1905, Vilhjálmur returned to Iceland with the Peabody Museum of Harvard as part of a large archaeological and physical anthropology research project. The group was excavating a medieval-era cemetery from the ‘Viking Golden Age’ that was on the tidal island of Haffjarðarey, located off the western coast of Iceland. Vilhjálmur’s interest was to study the teeth in the skulls to continue his examination of the relationship between tooth decay and diet. He was accompanied by a fellow graduate student, J. W. Hastings, who was conducting anthropometric measurements on local inhabitants. The collection is still housed at Harvard’s Peabody Museum and known as the Stefansson-Hastings collection. Stefansson continued his fascination with the relationship between nutrition and cultural factors in the Canadian Arctic, gathering detailed notes on the Inuit diet and conducting nutritional experiments, which he wrote about extensively. One of his last publications, near the end of his life, was titled, ‘Cancer, Disease of Civilization?’ in which he examined the potential health benefits of the ‘northern diet’ for preventing cancer. The book is still widely read today, sixty-five years after its first publication.

Soon after returning to Harvard, Vilhjálmur met a young Danish navel explorer, Ejnar Mikkelsen, who had come over to North America seeking sponsorship for a polar expedition to the Arctic. His imagination was ignited by Mikkelsson’s presentation of his plans to travel in the Arctic, and when the Mikkelsen expedition received funding, Vilhjálmur decided to join as an ethnologist, to study Inuit culture and society. Thus began Stefansson’s career of Arctic exploration.

Arctic Expeditions

Anglo-American Polar Expedition (1906-1907)

In 1906, Vilhjálmur embarked on his inaugural Arctic journey as an ethnologist, under the joint auspices of Harvard and the University of Toronto. Travelling to the Mackenzie Delta, he immersed himself in Inuit households, determined to survive the harsh winter on the land as the locals did. During his 18-month stay, Stefansson not only learned the intricacies of the local language but also adopted traditional survival methods, which would become essential in his future explorations.

Stefansson-Anderson Expedition (1908-1912)

In 1908, Vilhjálmur convinced the American Museum of Natural History in New York to sponsor a second, more ambitious expedition lasting 53 months. He was determined to immerse himself in Inuit culture, taking no supplies and learning to live as they did off the land. He was joined by his University of Iowa classmate, zoologist, Rudolph Anderson, who was fascinated by Stefansson’ ‘total immersion’ method of anthropological study. During this expedition, Vilhjálmur encountered an isolated group of Inuit, who still used traditional tools and exhibited more Caucasian physical features. Chronicled in his book ‘My Life with the Eskimos’, Stefansson speculated that these individuals could be descendants of the lost Greenland Norse settlement, sparking much controversy in academic circles and the popular press.

During these years, Stefansson relied heavily on the expertise and support of local guides and Indigenous communities, not only for his anthropological research but also for his physical survival. He hired a local man, Natkusiak, an Inupiat guide, who stayed with him for the entire four years and an Inuvialuit woman, Panigavluk (also known as Fanny Pannigabluk) who was a skilled seamstress. Although Vilhjálmur’s academic writings did not mention Fanny, or ‘Pan’, as he called her in his diaries, it is now well known that he had developed an intimate relationship with her and that they had a son, born in 1910, called Alex Stefansson. Most sources say that Vilhjálmur never formally acknowledged Alex as his son, but Vilhjálmur’s Innuit descendants consider the couple to have been married and note that he did not marry again until after Pan’s death in 1940. Pan and Alex were baptized in1915 by an Anglica missionary who recorded them as Vilhjálmur Stefansson’s wife and child.

One of Vilhjálmur ’s primary goals, in the 1908-1912 Arctic expedition, was to garnish the secret of thriving in such a cold, inhospitable environment. Vilhjálmur learned to speak the Inuit language and immersed himself in their knowledge of the land and the skills needed for living in the Arctic. During these four and a half years living in the Arctic, Stefansson adopted the Inuit lifestyle, living off the land, hunting polar bear and seal. He learned to kayak through the floating ice and to dog sled over harsh terrains. Later, in his writings, Stefansson emphasized the importance of adapting to the Northern climate and lifestyle through observing and adopting the ways of local people. He documented the local diet in detail and noted the exceptional physical and mental health of Inuit peoples. As important as the technical skills involved in thriving, Stefansson documented the social and cultural cohesion that underlay the well-being of Inuit communities. In his book ‘The Friendly Arctic’, he wrote that the far North is “a land in which children are born and live happy lives through to old age [so it] cannot be the terrible place of popular imagination.” Vilhjalmur grew to have a great respect for the Inuit peoples and spoke of their contentment living in what Europeans would have considered a harsh inhospitable environment. Much of his later written and lecture work was devoted to dispelling deriding myths of the Arctic and its people.

Today, the contributions of Inuit peoples to science and knowledge are being written back into mainstream historical narratives. We need to acknowledge the deep and enduring influence of Inuit knowledge, ingenuity, and adaptation to the Arctic environment and to redress the historical imbalance by highlighting the significant contributions Inuit peoples have made—and continue to make—to scientific knowledge of the Arctic. Vilhjalmur Stefansson contributed so much to our understanding and fascination with the Arctic, and he stands on the shoulders of the Inuit family and community which adopted and guided him on his fascinating journey.

The Canadian Arctic Expedition (1913-1918)

Vilhjálmur Stefansson organized his third and most ambitious expedition in 1913. There were over 100 scientists covering a wide range of specialities: ethnology, zoology, geologists, botanists, ornithologist, and oceanographers. There was, as well, numerous Inuit guides and hunters who would have been vital to the success of the project. The Expedition had ambitious goals for scientific and anthropological knowledge enhancement but also for mapping the continental shelf and looking for land amidst the ice. Originally, Stefansson was petitioning for American sponsorship, but the Canadian government stepped in and took over sole funding. At this time in history, there was international interest in ‘claiming land’ and Ottawa felt that if there was land under the ice, Canada should be the country to lay claim. It became known as ‘The Canadian Arctic Expedition’ and Stefansson was funded for a full five years. His colleague, Anderson joined him again, and led a southern expedition to document flora, fauna and geology, and to map inland territories. Both groups were to carry out ethnographic studies of local Inuit communities to learn about their tools, food supply, traditions and beliefs. Stefansson took a group northward to look for landmasses in the Beaufort Sea, facing great danger on sea ice as he searched for uncharted land which could strengthen Canadian sovereignty in the North.

Vilhjálmur’s northern expedition quickly ran into trouble. Right near the beginning of the expedition, in August 1913, Stefansson’s flagship, the Karluk became trapped in ice. After several days, in September, Vilhjálmur left the ship with a small hunting party, two sleds and a team of dogs to hunt for food. The Karluk was left under the charge of its captain, Robert Bartlett, a Newfoundlander who had spent over 30 years sailing in the North. Vilhjálmur meant for it to be a 10-day hunting trip. However, a storm set in, winds picked up and the ship began to drift helplessly in the ice. Vilhjálmur never found the ship again. Ultimately the Karluk drifted over 200 miles and finally, on January 14th, 1914, the ship was crushed in the ice and sank. To Captain Bartlett’s credit, the full crew of 25 on board survived, but as the group made their way across the frozen tundra seeking land, 11 men died. The remaining survivors made camp on Wrangel Island but were not rescued until September 1914.

Vilhjálmur was severely criticized in the press at the time for his decision to leave the ship. Vilhjálmur and his small hunting party survived the winter and made their way back to Alaska in a remarkable 600-mile sled journey. The expedition regrouped and, despite this calamity, Vilhjálmur continued with his explorations of the far North. He mapped thousands of square miles of the High Arctic, charting coastlines, measuring sea depths and currants, and gathering geological data. It is said that the Canadian Arctic Expedition resulted in some of the last significant discoveries on Earth’s surface. Stefansson laid claim for Canada to five “new” islands he discovered under the ice: Borden, Brock, Meighen, Lougheed, Stefansson. As well he mapped the Mackenzie King Islands and overall, significantly extended the map of Canadas’ Arctic Archipelago. Vilhjálmur Stefansson’s courageous and daring explorations extended Canadian sovereignty deep into the far North and laid the foundation of Canada as an Arctic nation.

Arctic Expedition’s Achievements

Over the course of his three expeditions, Vilhjálmur travelled more than 32,000 kilometres by sled and dog team, spending a total of ten winters and thirteen summers in the Arctic. He adopted a strategy of ‘drifting with the ice’, while extremely dangerous, was instrumental in the discovery of new landmasses, and to establishing Canadian sovereignty in the far North. Vilhjálmur became well-known for his "living off the land" philosophy, advocating that explorers could survive in the Arctic by adopting Inuit methods, and demonstrated that expeditions could be sustained by hunting and living in harmony with the environment, with the knowledge of Inuit guides. In his Arctic explorations he attained significant achievements, however internal strife, financial difficulties and the impact of World War 1, meant that Canadian government was not interested in a fourth expedition. Controversy also arose over a personal trip Vilhjálmur made to the far north where he laid claim to Wrangel Island. It causes a diplomatic incident as Russia saw this island as part of its territory. Vilhjálmur ended his Arctic explorations and returned to the United States where he focused on writing and lecturing about the Arctic. For the rest of his life, Vilhjálmur Stefansson continued to champion the potential and the promise of the Arctic.

Despite this alteration with Russia, when Stefansson died in 1962, during the period of the ‘Cold War,’ the staff in the Russian Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute in Leningrad sent Dartmouth College the following cable gram: “ With great regret we have heard about the death of the world famous outstanding scientist and investigator of the Arctic, Vilhjalmur Stefansson, The creator of the largest polar library. His name is always held in respect by the Soviet polar explorers. Together with you and widow Evelyn Stefansson we share the bitterness of this great loss.”

Literary and Educational Contributions

Vilhjálmur Stefansson was a prolific writer and tackled a wide range of topics related to his explorations. He is credited with writing 108 books as well as numerous publications, reports and articles. He was published in popular journals like The National Geographic Magazine, and in scientific and professional journals, making Arctic subjects accessible to both specialists and the general public. Some of his most notable books included ‘My Life with the Eskimo’ (1913) which chronicled his interactions with Inuit communities and provided valuable ethnographic insights. His famous, ‘The Friendly Arctic’ (1921), as its title implied, painted a picture of the North as a region worth living in and certainly worth developing. He wrote ‘Unsolved ‘Mysteries of the Arctic’ in 1938 in which he explored the lingering mysteries about the polar regions. Continuing his interest in what the North had to teach us about nutrition, Vilhjálmur wrote, ‘Not By Bread Alone’, in which he detailed the good health of the Inuit, where he observed there was no scurvy, heart disease or diabetes, and people had good dental health. This is still considered a ‘classic and essential reading’ for those interested in low fat, high protein diets. Vilhjálmur once spent a year living on a primarily meat-only diet as an experiment on his nutritional theories. In the last year of his Ife, Vilhjálmur wrote an article on the possible link between eating habits and cancer in modern society.

Vilhjálmur Stefansson was a popular speaker, known for being a witty and entertaining. He was invited to give lectures by universities, scientific societies and public forums across North America and Europe. His lectures combined vivid storytelling with scientific analysis, drawing on his personal experiences to educate and inspire. His goal was to dispel the myth of the far North as being a desolate and inhospitable land, and to capture the imagination of his audiences, not only with the beauty of the Arctic but its potential. He had taken thousands of photographs. It was one of the first Arctic expeditions to employ motion-picture cameras, giving a rare glimpse into Inuit life in the early 20th century. He was ahead of his time in his vision of possibilities of the North: he predicted air travel over the Arctic, submarines in its waters and great potential for economic growth. He also advocated for Canada’s strategic need to preserve its Arctic sovereignty. Central to his writings and lectures was the goal to foster a greater appreciation and understanding of indigenous knowledge and practices. Stefansson's ability to communicate complex ideas in accessible language made him an effective educator, and his lectures often led to lively debates and inspired further research in polar studies. He successfully advocated to set up polar studies at the university level. More on that in a moment.

Vilhjálmur compiled an extensive and comprehensive personal library which quickly became indispensable to universities, societies, officials and government agencies seeking reliable information on the Arctic. From 1932 to 1945, Vilhjálmur served as an influential advisor on northern operations for Pan-American Airways. In 1933, Vilhjálmur collaborated with famed aviator Charles Lindbergh, providing his expertise on Lindbergh’s ambitious plans for a transatlantic flight. Vilhjálmur's involvement showcased his deep understanding of the needs of and for Arctic aviation and highlighted his status as a leading authority in northern exploration and logistics. During World War II, Vilhjálmur took on a critical role as adviser to the United States government concerning northern defence operations, including cold weather flying and navigation for both aircraft and sailing ships. He conducted surveys of defence conditions in Alaska and prepared comprehensive reports and manuals for the Alaska Defence Force. He wrote a comprehensive Arctic Manual, for the U.S. military, providing realistic advice on how to survive if stranded in the high Arctic. It was published in 1944. Vilhjálmur Stefansson’s work ensured that military personnel operating in the harsh Arctic environment were equipped with the knowledge and resources necessary for success, directly contributing to North American security efforts during the conflict.

In 1946, he was contracted by the American Office of Navel Research to prepare an Encyclopaedia Arctica. He completed and published 20 volumes before the project was discontinued in the McCarthy era. In 1951, Stefansson was appointed Arctic consultant for Dartmouth College. He spent his final years at the institution, where he lectured, taught, and wrote extensively on polar topics, but one of his most significant legacies is establishing an Arctic library.

Stefansson Collection on Polar Exploration

Early in his career, Stefansson already had a large personal collection of books and papers on the Arctic. He was committed to making his library the best in the world, often searching for rare books and obscure publications in second-hand bookstores while on lecture tours around the world. His vision was to create a comprehensive collection that spanned the full spectrum of Arctic and polar research, from ethnology and anthropology, oceanography and geography to meteorology and navigation. Beyond his personal financial contributions, Stefansson’s reputation as an explorer and advocate for Arctic studies, enabled him to secure unique items. The American Geographical Society of New York donated over 300 duplicate publications to Stefansson, further enriching his library’s holdings.

By 1950, Stefansson’s library collection was so large, he began looking for an institution to take over the library. The collection was first transferred to the Baker Library at Harvard. A year later Darthmouth College, New Hampshire acquired the collection through the generosity of Albert Bradley, who was Chairman of General Motors and a trustee of Dartmouth College. His support ensured that the Stefansson Collection on the Polar Regions would have a permanent home under the auspices of a leading academic institution. It became the cornerstone of the new Dartmouth’s Polar Studies Program, of which Stefansson was made Director. Stefansson’s efforts led to the foundation for multidisciplinary studies on the Arctic which would include ecology, nutrition, ethnology, anthropology, geography, navigation, security and economic development.

The Stefansson Collection on Polar Exploration is considered one of Stefansson’s most significant legacies. It still maintains an international reputation as one of the finest historical collections on polar exploration and serves today as a vital resource for academics, historians, and government officials seeking reliable Arctic information. It is a testament to the power of his dedication, scholarship, and collaboration—embodying the spirit of discovery that Stefansson championed throughout his life.

The Last Great Explorer of the Arctic and His Enduring Legacy

Vilhjálmur Stefansson stands as a unique figure in the history of exploration, embodying both the spirit of adventure and the rigour of scientific inquiry. Known as the last explorer to discover new lands in the Arctic, Stefansson’s life and work has left an indelible mark on polar science, and the world’s understanding of northern cultures.

Canada, in particular, should be grateful for Vilhjálmur’s Icelandic courage, tenacity, determination and spirit of adventure. Vilhjálmur encouraged Canada to have a broader national vision of itself. Alexander Gregor wrote an article in ‘The Icelandic Canadian’ titled, ‘Canada’s Debt to Stefansson’. He said that “… the most important message Stefansson had, is that for Canada to reach its potential as a nation it needs to stop “huddling along the 49th parallel’, seize its own identity, and ‘come to think of itself as an Arctic nation’.” What Canada owes Stefansson is that he persisted in presenting evidence of the liveability of the North and its potential for economic growth.” These are words that should be ringing in Ottawa’s ears in these current times.

Vilhjálmur’s contributions to exploration and science were widely celebrated. In 1921, he received Iceland’s Order of the Falcon, one of the earliest recipients of this prestigious award. The Royal Geographical Society awarded him the Founder’s Gold Medal for his Arctic exploration, and he received numerous other awards and recognitions from American and European Geographical Societies. His status as a Fellow of many Learned Societies highlighted his acceptance into the global scientific community. He had received Doctorates of Law from six universities, included his first alma mater, the University of North Dakota. After his death, Vilhjálmur was designated a “Person of Historical Significance” by Canada, cementing his place in Canada’s national history. He secured Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic. The United States honoured him with a commemorative stamp in 1986, a testament to his contribution to the American nation.

Among Vilhjálmur’s most significant contributions was his advocacy for the value of Indigenous knowledge. He recognized the wisdom and adaptability of Inuit culture, promoting their practices and showing how their ways of living offered unique solutions for survival in extreme environments. Rather than imposing outside methods, Vilhjálmur respected the beauty and resilience of northern traditions, challenging prevailing attitudes and fostering a new appreciation for Canada’s Arctic peoples.

With fame came controversy. Vilhjálmur’s outspoken views and unconventional approaches sometimes placed him at odds with both scientific and popular opinion. Yet these debates underscore the complexities inherent in exploration: the tension between discovery and respect, between scientific advancement and cultural understanding. Vilhjálmur’s willingness to challenge norms has ensured that his legacy remains a subject of discussion and reflection.

In summary, Vilhjálmur helped map vast areas of the Arctic land and sea, promoted the value of Indigenous knowledge, and challenged prevailing ideas about survival in extreme environments. His respect for Inuit culture, advocacy for living off the land, and significant contributions to polar science have ensured his place in Canadian and Arctic history. Today, as society continues to grapple with the complexities of Arctic exploration and Indigenous relations, Vilhjálmur’s legacy serves both as inspiration and as a reminder of the challenges and rewards of venturing into the unknown. His legacy endures as a testament the enduring significance of the Arctic and the Inuit peoples, and to the need to reaffirm our commitment to understanding, protecting and celebrating one of Canada’s most remarkable regions.

Gwen Sigrid Morgan

INLNA President, 2025